Design Manifestos: David Reid of Gould Evans

David Reid is a Principal at Gould Evans in Kansas City, Missouri. David’s excitement about all things educational is contagious. He excels at helping clients envision a more compelling future condition: broadening their conceptions about the transformative power of great design.

David’s drive to create learning environments with real educational outcomes is reflected in his design process. His natural curiosity and patience engage clients and collaborators in a deeper understanding of a design problem, unlocking design solutions with meaning. Recognizing that the greatest innovations often emerge from constraints, he loves taking small projects and elevating them into major impacts that support a client’s mission. David is a leader in the firm’s research efforts into emerging 21st century pedagogies and how they interact with the built environment. Modelo spent some time learning about what inspires David and about his role at Gould Evans.

On becoming an architect

My mother is an artist, and my father is an architect and former professor of architecture at Kansas State University. He also taught furniture design and had his own woodworking shop in our home basement. These influences obviously exposed me to the joy of artistic and design expression at an early age, not to mention having access to high quality artist’s materials that make the act of creation more enjoyable. That access wasn’t always sanctioned, but the risk was well worth it.

As I got into middle school, I began to pester my parents for ways I could earn money. Hence, my first architectural contract; an architectural model for my father — a small office building. I was 12 years old, and I earned a whopping $20! My passion grew from there. I never questioned what career path I would follow. This felt so natural.

On discovering his voice as a designer

I was given some great opportunities to lead design early on in my career, but I can’t say I found my voice until much later. We were taught in school what good design is and isn’t, and looking back, the approach often resulted in trendy and dated design. It tended to be object-oriented rather than experience-oriented. To this day, it’s evident that many designers are consciously, or subconsciously influenced by the notable work that’s going on around them. It wasn’t until I started asking deeper questions about the social and humanistic opportunities inherent in design that I started moving toward more meaningful work.

I’ve also found more of a personal voice through our firm’s post-occupancy efforts; seeing how students value the opportunity to shape their own learning environment, and the level of engagement that ensues when they are allowed to do so, reminds me of my own childhood and my most memorable learning experiences. As a kid, I often used the scraps from my father’s workshop to fashion creative and dangerous constructs; a treehouse, a number of experimental rafts (that I should have never taken onto the lake), precarious rope swings, forts, and more. In reflecting back on those projects, it helped me realize the power of our environment to transform our experiences. Our firm’s education design work aspires to spark students’ imaginations and empower them to shape their learning habitats, in order to affect their personal learning experiences.

STEAM Studio, which is an experimental learning space for Science, Technology, Engineering, Art and Math located within our architectural studio, has been a powerful incubator for ideas. It’s also helped our design teams develop more empathy for teachers, and our education clients in general. Great teachers are heroes, but seldom do they get adequate recognition! And even more seldom do they get the guidance in designing learning spaces that can transform their teaching & learning efforts. This is where I find my passion as a designer — helping teachers to envision effective instructional environments that they have never considered, which better support blended learning and other changing pedagogies that they are being asked to adopt. We even get in the school’s business of teacher development and training, which is critical to successful adoption of a 21st century pedagogy and space.

Perhaps through all this, I’ve found my “inner teacher” — that dormant piece of DNA that I inevitably picked up from my father, the architectural professor.

On joining Gould Evans

Other than working with my father as a youth, my first job was with Gould Evans. I’ve worked elsewhere since then, but rejoined the firm 16 years ago. Since my father and Bob Gould, one of our firm’s founders, worked together at TVA in Knoxville back in the late ‘60’s, Bob and I go back a long way. In fact, I was probably 2 or 3 years old when I first “met” Bob. I’m sure I left a great impression on him at that time, but certainly the relationship has led to a lot of trust, and thereby opportunities to foster my professional growth.

I think the evolution of my approach is like a lot of architects…as you mature, you no longer feel the same urgency to use every crayon in the box on each project. The hand of mediation is an important asset in good work, to boil things down to their pure essence. Simplification. And seeking solutions that are driven by user needs, the user experience, and much less about form-making for form’s sake.

On specific principles he strives to adhere to

I’d say that I’m overly nerdy about how learning happens, which has piqued a deep and ongoing curiosity about the biology, neurology, psychology, and sociology of learning. Gould Evans strives for an evidence-based approach to our education design work, and we’ve found great value in the engagement of unconventional collaborators such as anthropologists, psychologists and industrial designers.

We also focus on developing more effective tools of engagement with our clients. Despite having a deep passion for and experience base in education design, we try to avoid making assumptions with each new client. We take a deep dive at the outset of each project; coming to understand the client’s culture, their student demographic, the unique aspects of their community, and their specific approach to this thing we call 21st century learning. This is the most powerful part of the process — the most likely place to innovate. And personally, the most enjoyable and entertaining part of my job. Teachers are such a blast to hang out with — they have their own brand of humor which has often been characterized as a survival strategy. I love it!

On his role at Gould Evans

My role is one of advancing our firm’s thinking about education design and adapting to the needs of tomorrow’s learners. We cross a wide breadth of education markets, from pre-kindergarten through higher education, and even life-long learning. It’s challenging, but also valuable since ideas cross-pollinate across grade levels, and it gives us broad insight into ideas from anywhere on that spectrum which help evolve education design forward.

On recent projects that represent the firm’s unique approach

I feel like we bring a unique perspective to the user experience of architecture. A great example is a renovation project in which we’re transforming what was originally intended to be a temporary hospital structure into a state-of-the-art campus for the Kansas City University of Medicine and Biosciences in Joplin, Missouri. The existing building is a kit-of-parts designed and built in 3 months after a tornado destroyed the city’s primary hospital. There was no attention spent on the human experience of its occupants. On top of this, medical programs are incredibly rigorous, and the incidence of depression among medical students is extremely high. So we asked ourselves how can we create a hyper-restorative learning environment that leverages design to help mitigate this phenomenon. This took us directly into discussions with psychologists who quickly translated their research on natural cures for depression, and helped us prioritize strategies such as community making, amplification of daylight, creating multiple scales of connection to the natural environment, creating “decompression spaces”, and providing a broad palette of spaces to support biological rhythms of students who are all on different sleep schedules.

Another example is a new STEM building for American River College in Sacramento, California. Their student base is diverse in academic ability, ethnicity, socioeconomic status and age. The campus is also host to a vital LGBTQ community. We asked ourselves what this diversity means to the ongoing discussion about design inclusiveness — how can we use architecture to help overcome many stereotype threats persistent among these groups and create positive outcomes for student success? Again, this sent us on a unique research path that led to ideas about neutralizing the hierarchy of classrooms, invigorating the interiors with inspiring graphics and vibrant colors, placing the entry level math labs in some of the best real estate in the building, and integrating the entry level programs with the advanced programs such that all students can see what options are out there and better relate their current efforts with a future path — and a future dream.

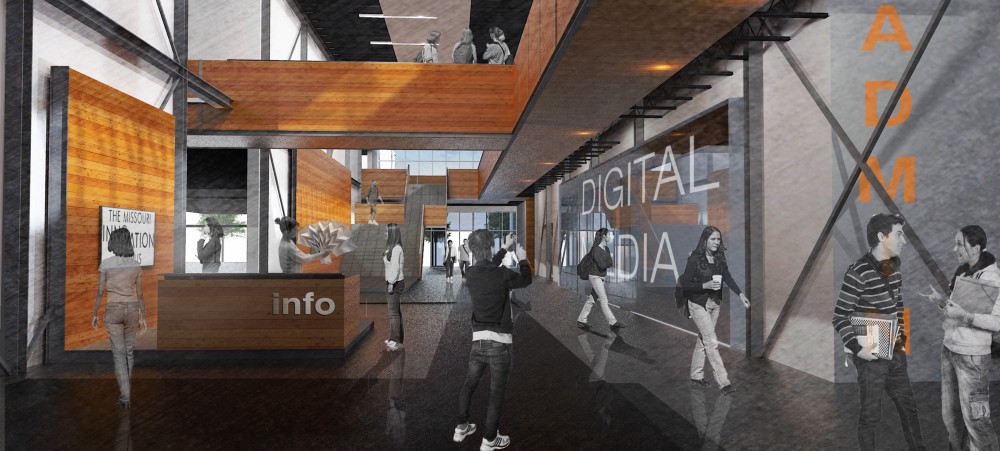

A third example is the Missouri Innovation Campus in Lee’s Summit, Missouri — the nation’s most accelerated college degree program. MIC places heavy emphasis on internships for credit and career readiness of their graduates. During the design process, we spent considerable time talking with business partners (internship hosts) to understand what career readiness means to their organizations, which we used to inform a series of design strategies that foster such skillsets in the campus setting. The result is a unique new facility where the faculty are challenged to be as progressive as the space that supports them, and where learning space looks like the workplace.

On his design toolkit

We live in a world where our clients have grown up playing video games and watching hyper-realistic animated movies. They’ve become very demanding in their expectations of visual representations, and are more expectant of looking at design ideas in 3 dimensions. The architecture profession is still playing catchup to other industries, and there’s no one single tool to get the job done. Within our firm, we use a crazy cocktail of programs in order to meet these client expectations. Our mainstay software programs include Sketchup, 3D Studio Max, Revit, and Rhino.

Collaboration across our large complex teams is another demand that drives our choice of tools. Recently, we had team members on three continents collaborating on the same project — it’s actually quite highly common to have team members scattered across three or four time zones. Getting all these associates to share the same model, and advance concerted ideas quickly for our fast-paced project schedules is incredibly demanding.

On the future of architecture in the next 5–10 years

Societal norms are changing rapidly compared with the past century. The expectations of Gen Y and Z youth are causing disruption everywhere: in education, in the workplace, and in the formation of society at large given their progressive attitudes about social equity and environmental issues. Architecture is being forced to respond to these changes.

These same pressures are going to affect certain markets quite heavily. Take the workplace for example: 72 percent of today’s high school students want to start their own business, and 65 percent of today’s grade school students will end up in jobs that haven’t been invented yet. The specific impact this will have on the workplace is up for anyone’s prediction, but it’s a topic we’re researching at Gould Evans.

Decision making is becoming more data driven and data justified. For example, in the design of workplaces: now that the negative health and productivity effects of open office environments are being published, we’re seeing a correction towards spaces that offer each employee more self-determination. We’re seeing more workers with nomadic careers, and we’re seeing an ever growing freelance workforce. The flexibility and “hackability” of co-working spaces for freelancers has influenced more traditional workplace environments.

In our schools, Roger Martin makes a great point about the creativity imperative for the future of capitalism, and how important creativity and entrepreneurialism are as a part of the education experience. Similarly, the International Center for Leadership in Education cites statistics about the reduction of mid-level jobs, and the necessity of empathizers and creatives to fulfill needs in the high-skills job markets.

On the future of Gould Evans in the next 5–10 years

At Gould Evans, we continue to broaden our circle of collaborators, bringing outside perspectives to the table to help us solve the complex challenges facing our clients. Our planning process is also becoming more complex and multi-disciplinary, as we are extending our role and guiding clients from earlier phases of project planning — earlier than architects traditionally get involved — in order to have more lasting impact.

On advice he would give himself

- Find people you really love to work with. Culture is everything!

- There’s a lot you can do as an architect, but at the same time, roles within the profession are becoming more specialized. It’s more and more difficult to be an effective “Renaissance Architect”. Design your path wisely to get you where you want to be, which may require seeking diverse experiences early on so you know what part of our profession best suits you.

- This iterative approach develops skills and patience that can be applied to career opportunities well beyond traditional paths in architecture.