Design Manifestos: Vishaan Chakrabarti of PAU Studio

Vishaan Chakrabarti, AIA, is a registered architect and the founder of PAU. Simultaneously, Vishaan is an Associate Professor of Practice at Columbia University’s Graduate School of Architecture, Planning & Preservation (GSAPP), where he teaches architectural design studios and seminars on urbanism. He serves on the boards of the Architectural League of New York and the Regional Planning Association. He is a trustee of the Citizens Budget Commission, and is an emeritus board member of Friends of the High Line. He is also a member of the Young Leaders Forum of the National Council on US-China Relations and has served on the National Mayor’s Institute of City Design. Metropolis Magazine named Chakrabarti one of the top 12 “Game Changers” for 2012, he is a former Crain’s “40 Under 40” and David Rockefeller Fellow. Modelo spent some time learning about Vishaan’s journey through the profession and about founding PAU.

On becoming an architect

As a child we traveled a great deal; my father was a scientist and when he had speaking engagements we would tag along. On a shoestring budget we saw the world’s great cities, with art, performance, and food always at the center of our travels. In an effort to be A-Good-Indian-Boy I majored in engineering in college, but eventually completed a dual degree in both engineering and art history, a kind of left brain/right brain path that ultimately led me to architecture and city building.

On discovering his voice as a designer

As an author I believe to write one must read, and it is the same with architecture — to “write” with design, and therefore to express one’s voice, requires the “reading” of cities and culture, materials and tectonics, places and occasions. For example, my architecture thesis examined the design of an eye hospital proposed by my father on the outskirts of Calcutta, India, in which patients would slowly regain their eyesight in the days following surgery; the project raised intensely architectural questions of the haptic versus the retinal in terms of light, materials, construction techniques, and the reading of the specific cultural landscape of the West Bengal river delta.

My professional influences span many of the great urbanist architects and theorists including Richard Rogers, John Habraken, Kenneth Frampton, the Smithsons, and other members of Team 10. A wide range of cultural figures are inspiring to me artistically, from painters Jacques-Louis David, Mark Rothko and Agnes Martin; to photographers Henri Cartier Bresson and Gary Winogrand; to sculptors Constantin Brancusi and Richard Serra; to musicians John Coltrane and MIA; to authors Gabriel Garcia Marquez, Jeffrey Eugenides, and Donna Tartt. Academically I have been privileged to study with extraordinary design professors including Stanley Saitowitz, Tom Chastain, Kathleen James Chakraborty, Gary Hack, and Julian Beinart. Beyond the field of architecture, certain individuals have been inspirations in terms of actions, words and demeanor, particularly Barack and Michelle Obama.

On starting PAU Studio

I started the Practice for Architecture & Urbanism (PAU) with the specific intent of founding a firm dedicated to re-imagining cities through enduring architecture and socially-impactful urbanism. Since the founding of the firm I have been energized by our collective ability to be true to our mission, taking only the commissions that provide the opportunity to help reinvent urban life. It will take some time for our current projects to be realized, but it is already evident to me that PAU will yield architecture that is specific to who we are and what we hope to achieve.

On specific principles he strives to adhere to

On our website, we have set forth a clear set of principles for our practice that are best expressed in terms of what we do and what we don’t do. We want to pursue cultural, institutional, commercial and infrastructural design projects that reinforce urban life. We are not interested in pursuing projects like suburban homes or office parks, casinos, correctional facilities, or commissions for nations or corporations with poor labor or environmental practices.

On his role as Founder of PAU Studio

As our founder my role is to lead our design work, mentor our team, and find commissions that align our ideals with our practice. I am also the bartender during our studio’s weekly happy hours.

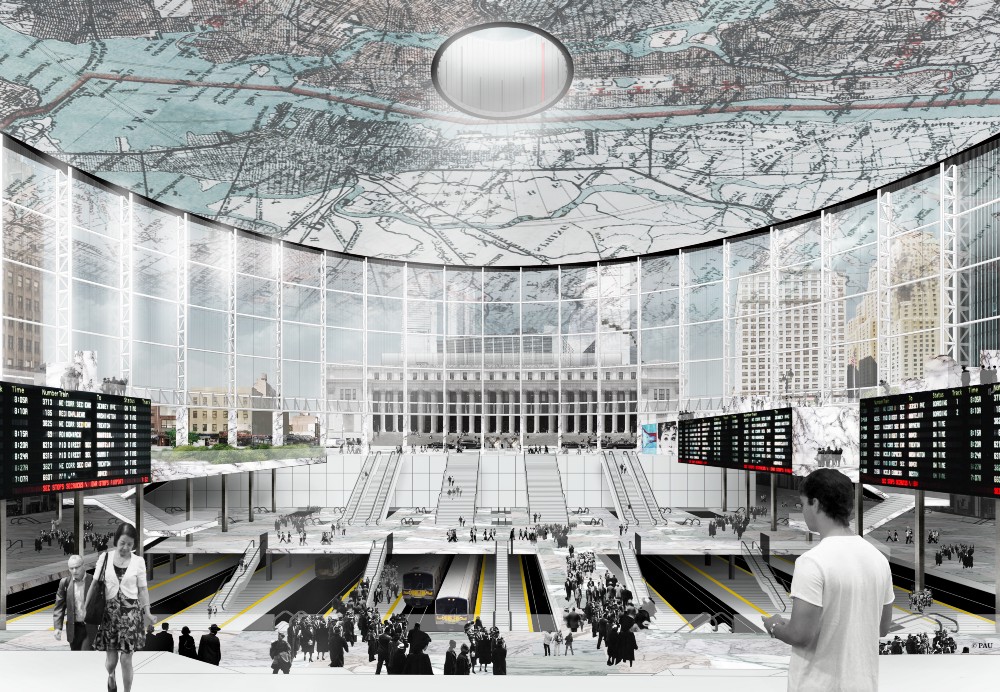

On recent projects that represent the firm’s unique approach

Our firm has a unique approach to design that explicitly entails the reading and writing of cities. The most representative project we can discuss publicly is our proposal to re-imagine Pennsylvania Station at the request of the New York Times. We made very specific architectural decisions governed by a palpable sense of self-restraint; we did not feel this building should be about PAU or its founder, but instead should be about arriving in the heart of New York City into the busiest transit hub in the Western hemisphere. As architects who believe deeply in urban public space we proposed the largest enclosed civic space in New York City, without a grand public price tag, by recycling the existing circular structure of Madison Square Garden once they have relocated to a new home. The specific architectural decisions include recladding the structure in a double-skin glass curtainwall to reveal the city from the station while passively heating and cooling it; the inner layer of glass would be arranged in a saw tooth pattern in plan in order to capture and reflect the specific light that strafes Manhattan’s side streets, colloquially known as “Manhattanhenge.” Conceptually this lightweight tectonic structure of roof, columns and glass would rest upon a stereotomic base rising from the below-grade platforms, culminating in a stone colonnade that would rise from the sidewalk level to create a durable and civic stone carpet around the entire perimeter of the cylinder, fluidly merging the space of the station with the space of the city. With inspiration from the stars on the ceiling of Grand Central, we have adorned the ceiling of the new Penn Station with a map of New York, orientating travelers as they emerge from their trains.

Our other projects include a major Manhattan mixed-use commercial tower with significant transit connections below; a Brooklyn office building with a vocational school at its base; a new transit connection across the East River; the design of a major public space in Midtown; the reconceptualization of a public housing site in Mexico City; master plans for major waterfront sites in San Francisco and Newark; and technologically futurist architecture and design for Sidewalk Labs. While none of this work is available yet for public release, we are confident that it represents a body of work that is indicative of a unique point of view in terms of both design expression and cultural meaning.

On his design toolkit

Our process often begins with me writing an essay about the project and the site, which usually includes observations about the project’s meaning, purpose and possibilities within the context of the city in which it is located. To supplement this essay, we generate sketches, photographs, collages, study models, and yet more sketches. Slowly we translate the site to the computer, typically using a combination of Rhino and Grasshopper. We tend to build three dimensional digital models prior to the creation of specific plans and sections on the computer, again moving back and forth between hand sketches and the Rhino model.

When the design reaches a certain point of maturity do we use AutoCAD for drawings, with painstaking attention given to line weights and dimensions. We try to avoid hyperrealistic renderings, opting instead for collages, section perspectives, axonometrics, diagrams, and other drawing types to communicate the design.

On the state of design software today

Design software is a powerful tool, no more, no less. We do not use software as a means to generate design, which comes much more from the head, hand and heart. Software is a powerful tool to resolve geometry, analyze problems, and express design intent. We imagine that the future will bring us more powerful software tools, but we do not imagine those tools as ever being a substitute for talent.

On the future of architecture in the next 5–10 years

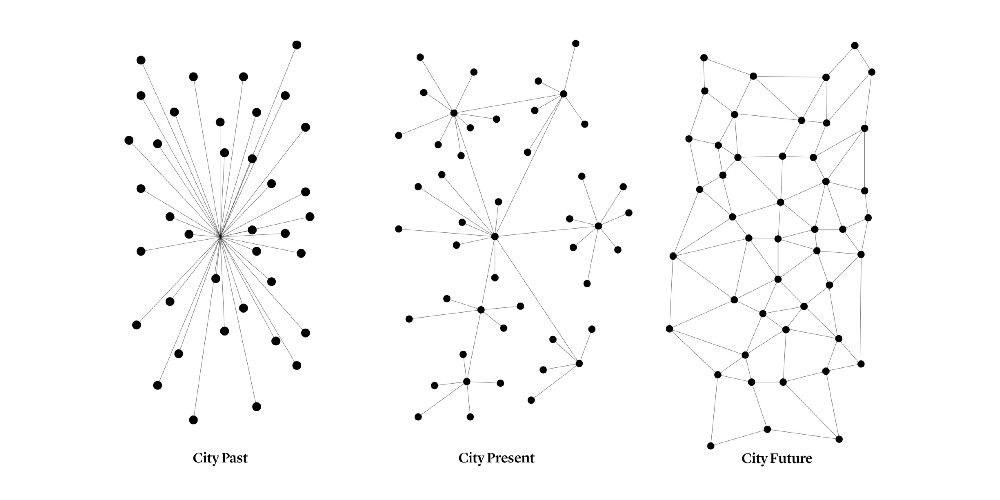

The language of architecture needs to become multivalent. To regain relevance architects could embolden design to be a horizontal rather than a vertical by reinventing their practices to bridge across the siloes of buildings, cities, ecologies, economies, and communities.

Design could be the cultural bridge that spans the gaping chasms of our time.

With the emergence of figures like Alejandro Aravena, Shigeru Ban, and Tatiana Bilbao, leading architects are bridging the false divide between design excellence and social impact that evolved out of the celebrity era of the late twentieth century. Our newest generation of designers, millenials, came of age at the outset of the twenty first century, when resource constraints returned to the fore as a consequence of economic and environmental hardship. The irrational exuberance of the nineties already feels distant, and with this new generation of young talent and new leadership, we will see a resurgence of design architecture with socially progressive ambitions, a reinvention of the idea that less can indeed be more.

On the future of PAU in the next 5–10 years

PAU will respond to the pressing and evolving challenges of our era. We will always strive to be a practice focused on social impact through the tangible advancement of cities, a practice naïve enough to believe that the very definition of lasting design is to create architecture and urbanism that will tackle society’s challenges and reimagine urban life in their wake. We exist to help reinvent the city of the future, to advance the values of liberté, égalité, et fraternité that undergird metropolitan life, to design cities, buildings, public spaces, infrastructure, and urban technologies that are of, by, and for the global civilization we seek to serve and advance. We take on this mission informed by our decades of experience, yet guided by the ideal that by reinventing cities, we can help shepherd our shared world to betterment, self-reflection, and public delight.

On advice he would give himself

To have faith in myself, my ideas and my design abilities regardless of what others think. Most of us struggle with this when we are young, and to prevail in that struggle is one of the great gifts of age.